Our Macbeth study guide has four parts that answer all the questions you have about the Shakespear's play. The guide includes a detailed summary of the storyline with the list of acts and scenes. It introduces the significant play characters and provides the analysis of their tempers and motifs. You’ll also find scrutiny of the thematic and symbolic range of the tragedy. Finally, we’ve gathered up the key quotes from Macbeth with the comments on their significance for the narrative.

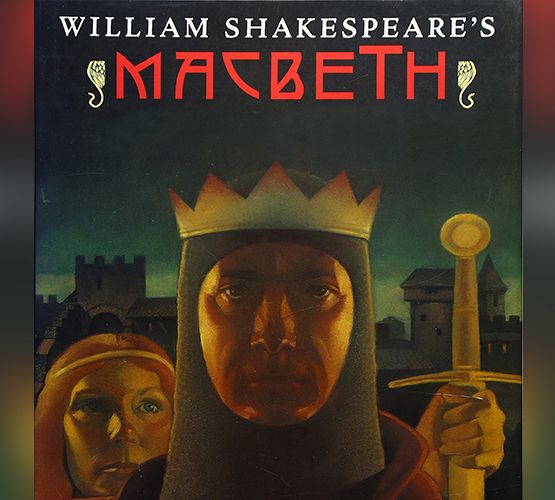

Macbeth by Shakespeare: Study Guide

Macbeth is the shortest play among all the tragedies William Shakespeare has written, and one of the most famous ones, too. The play dramatizes the destructive consequences of political desires on people who seek power for the sake of it. The play is said to have been written in 1606, a period when King James I had just taken over power. King James also happened to be the patron of the acting company that belonged to Shakespeare. Macbeth is said to be reflective of the close relationship that Shakespeare enjoyed with King James I, even though he had written many other plays during that time. Since Macbeth was a figure from Scottish history, the play is thought to be a means of Shakespeare honoring the Scottish lineage that his king originated from.

We’ve prepared for you a four-part study guide the play. The first part is an extensive summary of the storyline reflecting all the events of the play and presented act-by-act. The second part is the list of main and supporting characters with their description and profound analysis. In the third part, you will find a review of the main themes and symbols of the play. And the fourth part presents the key quotes from the original text with the comprehensive comments.

Before you get down to business, read a short summary of Macbeth that will allow you to get familiar with the main events through quick and clear description.

Complete Macbeth Plot Summary: an act-by-act Guide

For your convenience, we have prepared an act-by-act guide with a detailed description of the storyline. Of course, such a story summary can serve only as an additional tool and shouldn’t be the only source for you to get familiar with Shakespeare’s tragedy.

The approximate reading time is 30 mins.

Time needed to read the original tragedy - 4 hours.

Feel free to choose the topic.